We know the human recipe of Bruno Alvarez, one of the founders of the NGO ‘No Name Kitchen’

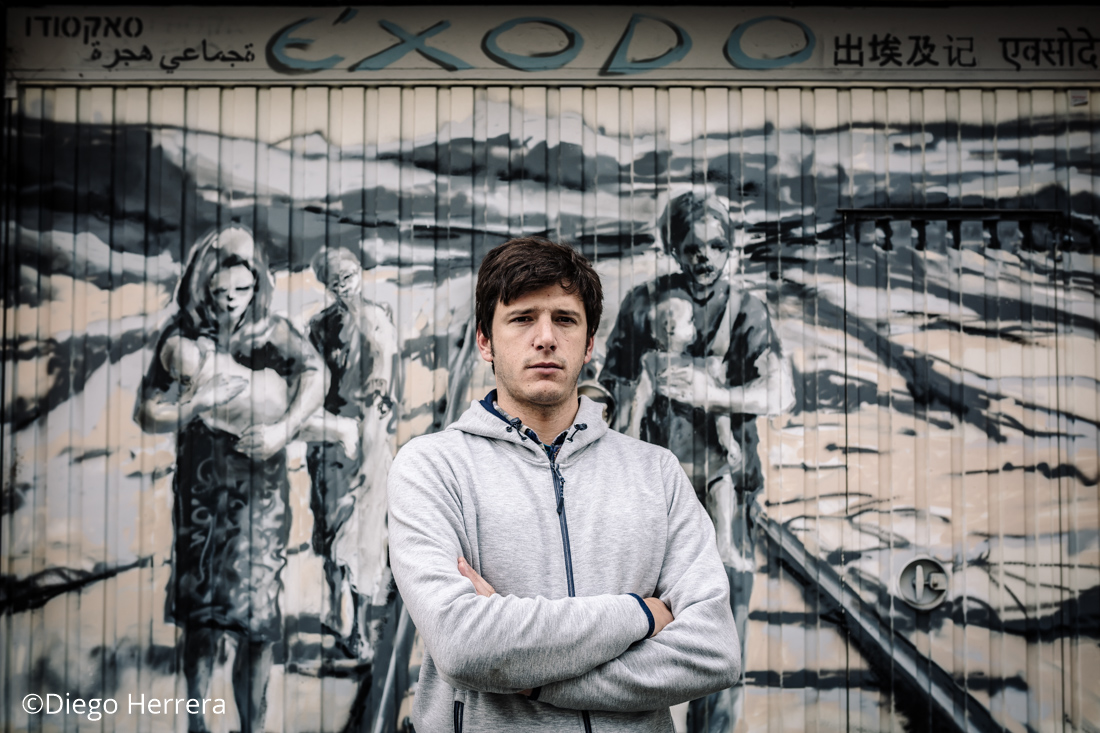

President and founder of the NGO “No Name Kitchen” / Diego Herrera

One’s present can be staggered when hearing Bruno Álvarez speaking about the situation of refugees in the Balkans. This young Asturian created -together with other volunteers- in 2017 the “No Name Kitchen” NGO. A project that has born when he saw with incredulity how the refugees lived while transiting people whose origins have been moved to the barracks of an old train station in Belgrade. Since the beginning, this NGO has grown as injustices have increased and so, Bruno’s testimony, which will be part of the history.

Newscasts bomb us with information, numbers and figures without names or linked stories. However, Bruno’s words describe the real situation of these people, what they have to face and how with human warmth, his organization “No Name Kitchen” receives and accompanies with a plate of hot food, creating a safe and trustworthy place.

The temperance in his words and his confidence in the good work, draw a smile to this crude reality. It is clear to him, and he proves it to us, that no matter what he will continue fighting to dignify the lifes of these people, with the different projects that the “No Name Kitchen” develops in Patras (Greece), Sid (Serbia), Velika Kladusa (Bosnia), Ceuta, Melilla or where necessary.

Question. What takes a flight attendant to pack his life and decide that Serbia would be his next stop?

Replay. What took me to this point was a video my mum sent me through Whatsapp. A video showing the situation in Greece’s camps. I don’t know if it was Lesbos or where it was, but I know it lasted about 6 minutes and that before the video was ended I couldn’t hold back my tears.

At that moment I thought ‘I have to go and see what is happening’. So, I decided to go for 15 days first, to the Piraeus harbour. There, at that time, I lived with people who were trapped and crowded. After 15 days I returned home and decided that the next flight would be without a return ticket. Our first stop was Athens for five weeks, and in the sixth week we headed towards Belgrade.

Q. Why “No Name Kitchen”?

R. The “No Name Kitchen” came up in a totally sporadic way. As volunteers, we were doing different activities in Athens, when we recieved few images of Belgrade showing quite unfortunate situations. This, added to the fact that the government had issued an open letter prohibiting any kind of assistance…we thought it was crazy. That’s when we decided to go there.

We started as a group of 6 people, just with some jackets and a van that was due to take back the following week. When we arrived there, we analysed the situation, and we saw that they were in need of a hot meal for dinner. It was a particularly cold night, with temperatures reaching minus fifteen degrees. We thought of a cook friend, who was in Athens cooking for many people, we called him and he accepted to come and help. The first steps, were to go and buy food, adapt the place where we were going to cook and put the pots to heat. In those moments between fires someone pulled out a spray and asked “what are we called and who are we?”, because if we don’t have a name, “No Name Kitchen” will be our name. Currently we still keep that first sketch in our logo.

No Name Kitchen / Diego Herrera

P. If you had to choose three words that define your first impression in the fields, they would be…

R. What we felt as soon as we arrived was a shock, accompanied by a situation of ruin and desolation. In the same place to sleep you could find excrement, garbage and rats.

Q. What is the situation of these people living in Serbia, Bosnia and Patras?

R. There you meet people who are desperate but motivated because they are in transit countries that allow them to reach their destination. They have that motivation to go on their way, to be able to find a place where they believe they would live better. There are also people who, little by little, loose all their motivation due to blows and hardship and living in unsustainable conditions.

You have the motivation, and you go again and again, but when you are deported 20 or 30 times, when you have been robbed, when the people who were in your way have crossed and you do not get it and you are left behind, your head is shrinking. We are seeing people who unfortunately have lost their way. “Thanks” to our European Union policies, we have driven them crazy.

Q. What is the attitude of the Serbian, Bosnian and Greek government towards your work and refugees?

R. They are three very different countries, Serbia and Bosnia are more similar. Unlike what we do in Patras, done with the support of Patras’s City Council, governed by a left-wing political group.

In Patras they give us a lot of support for the food issue, we can have refugees at home if we want, they do not come looking for them. In Serbia it is quite the opposite, we cannot have migrants at home, they control us and persecute us. This affects the refugee people in the same way, as they are taken to closed camps far away from society. As an entity, we perceive the two sides of the coin, on one hand the support of the Municipality of Patras and on the other one, the ongoing struggle with the governments of Serbia and Bosnia.

Q. How are volunteers and refugees treated by the local population?

R. If we talk about Serbia, at the beginning there was total indifference, we didn’t notice the presence of social resources, and they didn’t pay much attention to us. When we moved to Bosnia, the general feeling at the arrival of the first volunteers, who arrived after several months or even more than a year, was one of warmth. In an interval of four or five months, the situation changed, the tension was latent in many places, more racist movements and policies were promoted. Society began to erect certain walls to these people on a day-to-day basis.

Bruno during a meeting talking about No Name KItchen (Velika Kladusa)/ Diego Herrera

Q. How European policies affect this population?

R. They are direct builders of “human corridors”, millions of people walk a lot of kilometres “thanks” to this type of policy. Through the agreement with Turkey and the European Union we armor our fortress called Europe, so we force people to use illegal and unsafe ways where they put their lifes at risk. This enriches the mafias who make high profits from these extremely vulnerable situations.

Q. What do refugees flee from?

R. We share our daily lifes with people who flee for very diverse reasons, such as religion, sexual orientation, climatic disasters, ideology, family disputes, Taliban or dictatorial regimes… In short, situations which do not allow them to be developed as human beings. As a society, we need to generate welcoming policies and stop seeing it as a burden, because it is an opportunity for demographic growth.

Q. Who can be the culprits?

R. It is a guilt shared by our way of life, by our abusive capitalism and crazy consumerism. We want to have the latest model of mobile at all costs forgetting where the lithium of the battery comes from. That necesity of producing and consuming lead us to squeeze countries and exploit their lands, contemplating them just for their most precious goods, but not for their their people.

Q. What measures would you take to solve this situation?

R. I would invest all the money that is used to protect our borders, in generating a welcoming structure, training opportunities, linguistic support or legal channels to promote a dignified life. That money in fences, borders, personal, does not stop these people from trying to pass.They will keep trying, because they won’t turn halfway back.

Q. What can we do as a society to repair or solve this situation?

R. Make them aware that there is humanity and affection in this generally dehumanized “adventure”. A plate of food, clean clothes, a hot shower… these are the means we can use to talk and share personal concerns or experiences. Being there and listening, empathizing with those migrants who years ago could be our closest ancestors.